In the previous part on the global shortage of chip supply, we have had a look at how extremely difficult it is to build a chip factory. Today let’s have a view on a bigger picture, a geopolitical one. On Friday, Dec 18, 2020, the United States government placed harsh restrictions on Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC – 中芯国际), China’s biggest chip manufacturer, effectively cuts them off from US suppliers and technology [1]. SMIC shares sank 10% in Hong Kong in one single week. This strike is just another in a series of sanctions that sparked firstly in 2017, heated up during the Trump administration, and is widely known as the US-China trade war.

This trade war between the US and China is a controversial matter with different opinions from multiple sides, and will not be the central focus of this article. Today’s reading is more about the semiconductor industry of China – how it has grown from a struggling third world country to the present position that threatens even the most powerful states of the modern world.

“That is a sleeping dragon. Let him sleep, for if he wakes, he will shake the world.”

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821)

The rise of China

Before diving into China semiconductor’s industry, it is worth having a look at all the changes that happened in this special East Asia country in recent decades. February 1979, NASA’s Johson Space Center is welcoming the visit of a significant VIP guest: People’s Republic of China’s paramount leader Deng Xiaoping (邓小平) [2]. Deng became the first Chinese leader ever to tour the USA. After 30 years of isolation, China is suddenly back on the international stage. And Deng is making it clear to the world, that his country is now open for business. At that time he doesn’t know yet that his approach will work, beyond all expectations.

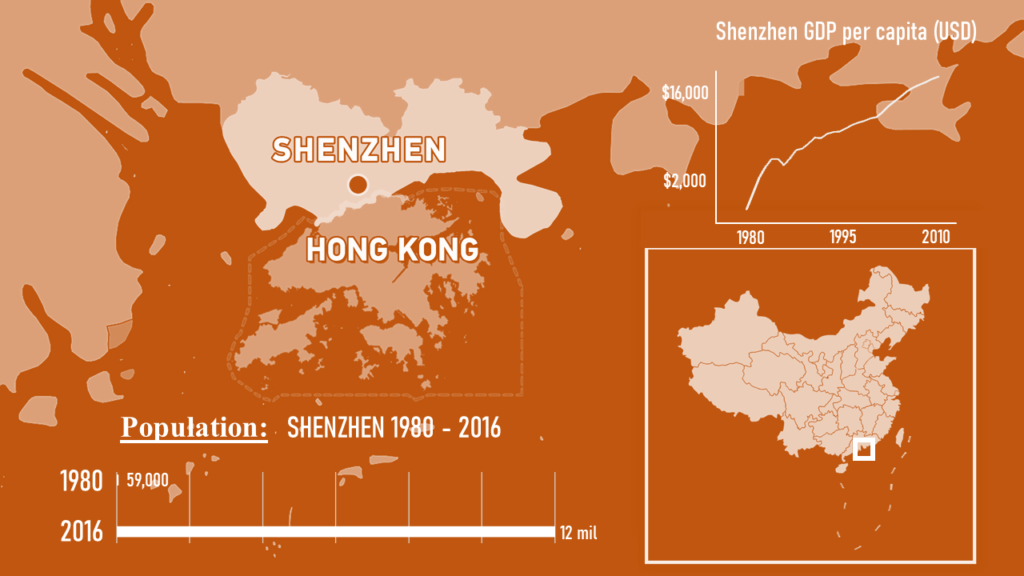

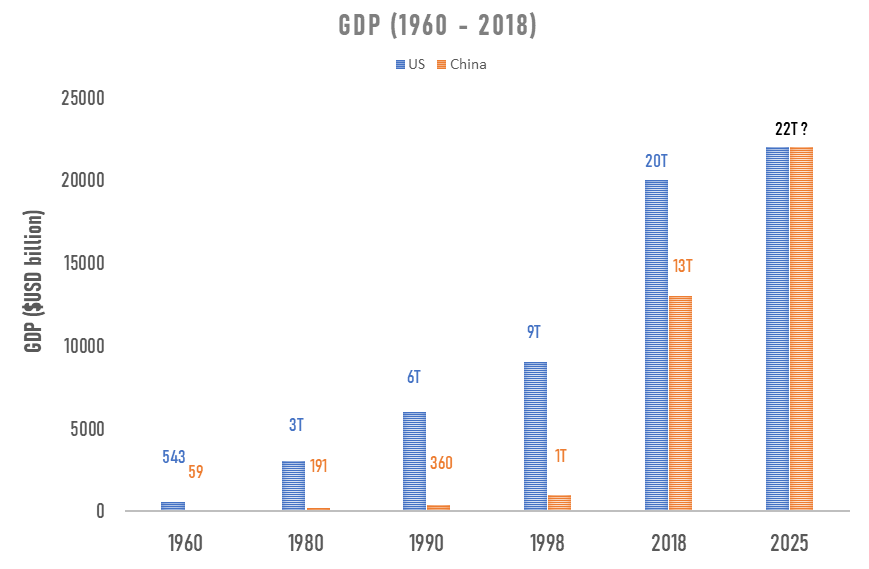

In 1960, China’s economy is worth $59 billion, a figure dwarfed by the US economy worth $543 billion at that time. Deng initiated an economic reform, begin by creating four Special Economic Zones (SEZs): Xiamen (厦门), Shantou (汕头), Zhuhai (珠海) & Shenzhen (深圳) – the city that will later be known as the Silicon Valley of China. These zones are allowed to play by different rules, where companies & factories are able to import & export goods to the West. They will serve as mini economic engines for the rest of Communist China. And it proves out to be an effective strategy, doubling China’s GDP in the period of 1980 to 1990, from $191 billion to $360 billion [3]. But so does America, having its GDP at $6 trillion at the beginning of the 90s.

Over the next 30 years, China develops more and more of these development zones. By 2005, China is constructing neighborhoods the size of Rome (1,285 km2) every two weeks. Between 2011 and 2013, China uses more cement than the entire US did in the 20th century (6.6 vs 4.5 gigatons). China currently owns 15 among 47 megacities (cities with over 10 million people) in the world. And in the top 10 largest seaports of the world, 7 belong to China, with the first & second places are Shanghai & Ningbo-Zhoushan respectively.

In 1998, China’s economy hits the $1 trillion mark, while the US is $9 trillion at that point. However, the overall wealth of China has been increasing at an astronomical rate, reaching $13 trillion in 2018 while the US is $20 trillion. It’s not a matter of if, but when China will overtake the US.

Huawei – the Giant

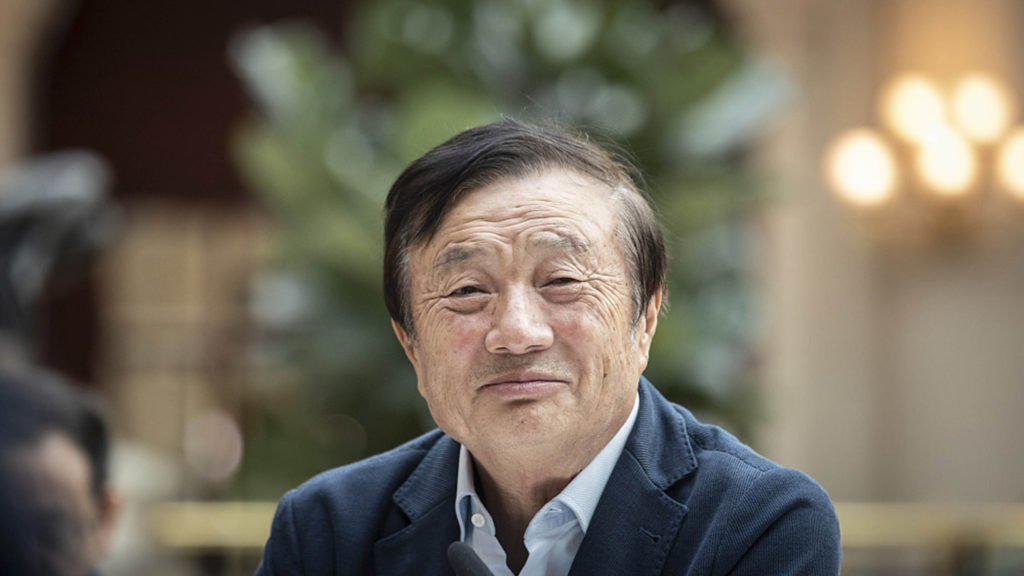

During over three decades of its existence, Huawei has been going through an impressive endeavor to become the most symbolic monument of China’s semiconductor industry. The marvel of this company comes from its intensive struggle to survive, just like the life of its legendary founder Ren Zhengfei (任正非), an inspiring journey that can be anything but easy.

Ren was born in 1944 in a remote mountainous town in Guizhou province. In 1963, he studied at the Chongqing Institute of Civil Engineering and Architecture. After graduation, he was employed in the civil engineering industry until 1974 when he joined the military’s Engineering Corps as a soldier tasked to establish the Liao Yang Chemical Fiber Factory and was lastly promoted to Deputy Director [6]. The pivot point came in 1983 when the Chinese government disbanded the entire Engineering Corps, Ren Zhengfei now 39 years old, found himself abandoned in the effort of reintegration with the market economy. He then worked in the logistics service base of the Shenzhen South Sea Oil Corporation. As he was dissatisfied with his job, he decided to establish Huawei with a capital of just CNY21,000 in 1987 (around US$5,000 at that time [7]). The name comes from the slogan 中华有为 (Zhōnghuá yǒuwéi) – ‘promising China’.

“Switching equipment technology was related to national security, and that a nation that did not have its own switching equipment was like one that lacked its own military.”

Ren Zhengfei to Jiang Zemin (1994)

In 1990, Huawei started to produce its very first product: telephone exchange switches, winning a small contract with the People’s Liberation Army but large in terms of relationships. However, instead of cooperating with a foreign company like many Chinese companies at that time were doing, Huawei invested heavily in R&D to manufacture its own technologies. These investments slowly became intolerable to several Huawei leaders, in which many of them urged the CEO to focus on PHS (a low-cost handphone system that has now been outdated) instead of his 3GPP vision. According to Ren, there were times that the pressure from his work drove him to the brink of depression and collapse.

Huawei’s expansion to the European market after the 2000 Dotcom bubble has brought it many fruitful successes. The first joint innovation center between Huawei & Vodafone was set up in Spain in 2006. In 2009, TeliaSonera, the Swedish telecom giant decided to cooperate with Huawei to deliver one of the world’s first LTE/EPC (later evolved into 4G) commercial networks in Oslo, Norway [9]. Huawei quickly became a favorite choice by many countries to develop their telecommunication infrastructure, including European cities whose network has previously been constructed by renowned companies such as Nokia and Ericsson.

“At the time, the hourly rate of consultants was US$680, which was equal to my monthly salary. But to prepare for the future, we had to learn from others.”

Ren Zhengfei

Besides telecommunication, the 3GPP technology that Huawei invested in started to pay off when China authorized the first 3G license in 2009. The U8220 was Huawei’s first Android smartphone and was unveiled in MWC 2009. Its first Ascend smartphone was introduced in 2012, marking the era of China’s rise in the semiconductor industry. Now Huawei is able to make its own competitive chips, with its mysterious but excellent child – HiSilicon, the largest fabless semiconductor company in China.

HiSilicon – the Dark Horse

HiSilicon (海思) is an enigmatic company that works similarly to the chip design department of Apple. It is a fabless team that designs processors based on ARM architecture and manufactured by the latest technologies of TSMC, powering the devices of its owner Huawei. It originated from the IC Design Center of Huawei founded in 1991. After a 2003 lawsuit by Cisco, Huawei CEO Ren Zhengfei resolved to establish a chip design division to reduce his company’s dependency on American chips.

In 2009, HiSilicon brought out their first mobile phone processor: the K3. It was a low-cost chip that targeted low-end markets. Three years later (2012) came the 2nd iteration of that chip, the K3V2 (40nm). Huawei bravely announced that they will put this chip into their new flagship mobile phone: the Huawei Ascend D Quad XL, instead of using chipsets from well-known companies such as Qualcomm or MediaTek. A decision that took courage, but didn’t pay off at first. The K3V2 frequently overheats and is nicknamed ‘warm baby’. In 2013, the company released a new iteration called the K3V2e which powered the Huawei P6. This P6 sold well and was the first taste of processor success for Huawei.

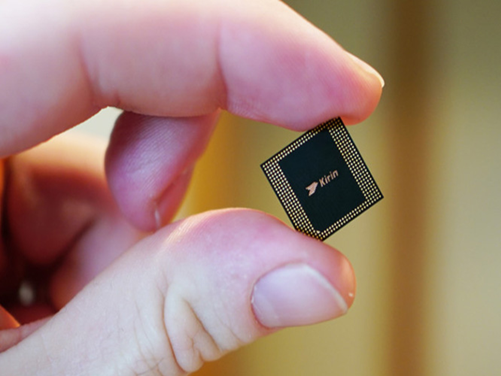

After the achievement in the smartphone market, HiSilicon rebranded the K3 series to Kirin (Qilin – 麒麟), a reference to an East Asian mythical beast. Kirin 910 (28nm) was their first SoC (system-on-chip) design and integrated 4G baseband components, utilized by the Huawei P6s and Ascend P7. The rise of Kirin coincided with the success of Huawei’s smartphone line, helping it compete directly with Samsung Galaxy S-series. The Mate 10 (announced in Oct 2017) used Kirin 970 (10nm) and was sold over 10 million units over 10 months. The latest version of Kirin from HiSilicon is the Kirin 9000 & 9000E (5nm) was released in 2020 with an impressive 15.3 billion transistors, 30% more transistors than the Apple A14 (used in iPhone 12), powering the company’s Mate 40 & 40 Pro.

HiSIlicon’s success with the Kirin line led it to expand into other chip markets. In 2018, the company released its first AI chip, the Ascend (Shengteng – 昇腾) series. These AI chips utilize a specialized structure to help speed up the training of AI models. Another interesting product line is HiSilicon’s entry into the profitable server and desktop market: a year after the Ascend launch, this company introduced a series of ARM-based chips for server farms, called the Kunpeng (鲲鹏) – another Oriental mythical beast. The Kunpeng 920 (7nm) powers the 2,000 Huawei TaiShan servers running Beijing’s e-government system [14]. Recently, Kunpeng chips have also started to appear in Huawei desktop PCs sold in China that favorably compares to Intel’s chips in certain multi-threading benchmarks [15].

Conclusion

The global chip crisis is a wake-up call for countries around the world about the importance of semiconductors to their future. The US government is already rolling out actions to choke off chip supplies to the Chinese champions, including SMIC and the giant Huawei. TSMC has had to stop its Kirin 9000 shipments to HiSilicon on September 15th, 2020, according to the sanctions of the Trump administration, losing its second-biggest customer after Apple. Companies and countries are going to clash for years for semiconductor supremacy. How will China’s chip industry survive in the long term? Will it collapse under immense pressure or will it break out and construct its own empire? Whatever its future, it’s safe to say no one is ignoring China anymore.

Reference:

- US bans China’s top chipmaker from using American technology. Jill Disis, CNN Business. Dec 18, 2020.

- This Day in History: Deng Xiaoping’s Historic Visit to the US. Jonathan Zhong. Jan 29, 2021.

- China GDP 1960-2021. macrotrends.net

- Shenzhen sees 20.7% annual GDP growth over 4 decades. Xinhua. Sep 25, 2020.

- New chart shows China could overtake the U.S. as the world’s largest economy earlier than expected. Evelyn Cheng, Yen Nee Lee. Feb 1, 2021.

- Mr. Ren Zhengfei – Huawei Executives. www.huawei.com

- Li Hongwen (2019), p. 26.

- Ahrens, Nathaniel (February 2013). “China’s Competitiveness Myth, Reality, and Lessons for the United States and Japan. Case Study: Huawei” (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Milestones”. Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016.

- “Who’s afraid of Huawei?”. The Economist. 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

Huawei has just overtaken Sweden’s Ericsson to become the world’s largest telecoms-equipment-maker.

- “Huawei expects ‘eventful’ 2018 to deliver $108.5bn in revenue”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- “Hisilicon grown into the largest local IC design companies”. Windosi. September 2012. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Analysts: Huawei booms to No. 3 worldwide smartphone maker with P6, G610 success. Phild Goldstein. Oct 29, 2013.

- “TaiShan 2280 V2 Balanced Server ─ Huawei Enterprise”. Huawei Enterprise. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Huawei’s Upcoming 24-Core Kunpeng CPU Faster Than Intel Core i9-9900K. Joel Hruska. Aug 11, 2020.